Can't I do pronunciation later? or Why children are different

Seems such a pain. Not only do you have to struggle with new words, genders, lenition, prepositions that conjugate, irregular verbs, question particles, two ways of saying my dog, two ways of counting, a new way of looking at the world, but also pronunciation, and so little time for everything.

So why add pronunciation to all that when you could happily ignore it until later? Or can you? By now, depending on how well you know Akerbeltz, you've probably guessed the answer is a resounding you can't. Unfortunately. Believe me, I'm not taking some kind of obscene pleasure in telling you this to initially make your life more complicated. Clear pronunciation will make your life easier and lying to you would be counter-productive.

There are two things you need to understand about this. The first one is about native speaker acceptance, levels of tolerance and what YOU want. The second is about pimples, puberty and phonology.

Tolerance and What YOU Want

Why are you learning Gaelic? Do you want to be able to hold a small conversation? Do you want to use it for trading and simply need some stock phrases and numbers? Are you going on a holiday and want to be able to read road signs? Do you want to become fairly fluent or fully fluent so you can communicate in a different language? Or do you want to work or live in a different language community and want to integrate better? Are you "chasing your roots"? Do you have children in Gaelic medium Education and want to help and understand them? Are you trying to prove your Scottishness?

There are many reasons why people learn languages, probably as many as there are people. So far, so good. It's also true that for very basic communication you do not need much more than a smattering of words and phrases and you can ignore things like grammar and phonology for the most part.

But as soon as your aim is a medium to high level of fluency, both grammar and phonology (the way the sounds of a language work together) become far more important. At this point, it begins to influence the way people perceive you as a language learner. The degree of accuracy you achieve will directly raise or lower your "linguistic standing". For example, a friend of mine still recalls the day he was having a conversation with a number of people who kept asking him "how deep?" every time he said "I think" – because being a native German speaker he kept saying "I sink". We have all heard jokes like that, people everywhere on the planet make them. Not necessarily because they're mean or vicious about other people speaking their language because in most cases people will be very pleased you're trying to speak in their language. But, there are those times when the words coming out of the foreigner's mouth is just plain and simply funny, as when the poor European tried to say "one year has four seasons" in Cantonese and had the whole room laughing. He got the oh-so-important tones wrong and as it turned out that he'd actually said that "one lotus has a dead turtle". When they explained this to him, he had to laugh himself.

But there is even more to it. Speakers of English are accustomed to hearing a huge number of different accents of English becuase it is the Lingua Franca of the 21st century. So, in a way, a variety of English accents doesn't matter that much. But, generally, speakers of minoritised languages are not accustomed to hearing anything but native speakers. Usually, languages like Gaelic are not learned by adults, or at haven't been in the past.

Although making grammatical mistakes is something we all do, even in our native language, people very rarely produce sounds that are not permissible in their native language. No matter how drunk you get, you will still be obeying the sound laws for your language (in the drunk's case, the rules for slurred English).

So, while many native Gaels are lax about their grammar in some respects, they all intuitively have correct pronunciation. Thuit an dà bhròg air an t-sràid nuair a bha 'dol dhachaigh is perfectly good Gaelic, never mind the lack of the dual number slenderisation in bròg, and dropping vowels - this is spoken language we're talking. If they now come across a learner who has perfect pronunciation and slightly shaky grammar, they feel "at home" and will communicate with the learner, in relative comfort. On the other hand, you, the learner, can cause our poor native speaker no end of pain if your grammar is 100% perfect but your pronunciation is ghastly. And, as a result, you're immediately identified as an "alien invader".

While this shouldn't encourage you to ignore correct grammar, on balance it's the lesser evil of the two. It really pays to drill yourself in correct Gaelic pronunciation even if it slows you down, initially. In some cases, your ears may never learn to hear the difference between the 3 Gaelic L sounds, but at least you can learn to make them correctly so they will "sound right" to a native speaker.

Incidentally, there's another subtle difference between an average German learning English and an average Scot learning Gaelic. Hardly any German is learning English to "recover their ancestral tongue", if you pardon the flamboyant expression. But most learners of Gaelic have some sense that they are re-learning a language they ought to have learnt as children - so their aims are totally different. The German is acquiring a tool to travel, work, and so on. Tbe average Gaelic learner is trying to achieve fluency in his or her "native" tongue, so bad mistakes take on yet another dimension.

Why Children are Different

We all know intuitively that children are so much better at learning languages. After all, we've experienced this ourselves. We all speak our native languages fluently without being able to explain what a low falling tone is, what an ergative is, and why English has irregular plurals.

This unfortunately has led some people to deduce that adults are so much worse at learning languages because we do not learn them the "natural" way children learn by listening, emulating, jabbering a lot, no pens, papers, vocabulary lists and declension tables. Erm ... isn't that a bit like saying that the lawn is wet because the sprinkler was on in the morning and deduce that the wetness, now, is because the sprinkler had been on? Not really, it could have been raining ...

Children do learn their native language(s) in the said way, even if you can't get two linguists to actually agree exactly how they do it. But, unfortunately for us, whatever the childhood mechanisms are, they operates within a very short time window. Remember the bit about pimples, puberty and phonology? In a nutshell, we lose the ability to acquire languages as native languages, perfectly and without needing formal instruction, around the time we reach puberty.

But, at the same time, we gain something lovingly referred to as Cognitive Skills meaning powers of analysing, structuring, ordering, seeing patterns, memorising in a structured way, and the likes. This doesn't mean that children are stupid, we just get much better at using cognitive skills during puberty, and beyond. Which is why people in many parts of this world, and over time, from the Sanskrit grammarians to the first Chinese dictionary written in 100AD, from ESL programmes to Adult Immersion Courses in New Zealand, teachers have used tables, pen and paper to hammer something into our heads that would have been best and easiest learned when we were 4, but, for whatever reason, we're trying to learn now. These cognitive aids are necessary and not used because language teachers are sadists (although some might well be!)

This time window, from birth to around puberty, affects every aspect of languagelearning including grammar, vocabulary, phonology and phonetics. Post-puberty, we have to drill ourselves when we come to learn a new language, because we don't just pick it up anymore the way we used to when we were 4. But this still doesn't explain why you can not leave pronounciation until later - or does it? In a way it does. Think of Gaelic as an empty database in your brain which you gradually fill with data including words, sounds, how to make the sounds, and how to put it all together. Now, if you start building your database and fill it full of words with the wrong pronunciation, because you've decided to leave it until later, what do you think will happen later when you decide to improve your pronunciation? It gets tricky. Your brain has already stored hundreds if not thousands of entries by then and you'll need to edit them all. And, the editing we're talking about here is not as straightforward as going into the MS Office Custom Dictionary and amending the entries. Perhaps it's not impossible to amend incorrect pronunciation, but it's very hard and nearly impossble. Wouldn't it be so much easier to store things correctly, in the first place? I'll leave you to decide that.

"Older is Faster but Younger is Better"

This is just an addendum if you want to know more about this puberty cut-off. There's a lot of research out there to prove all this, but one of the best ones I've come across, so far, is by Snow, Hoefnagel-Höhle (1982) The Critical Period for Language Acquisition (in Krashen, Scarcella & Long (eds.) Child-Adult Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, Newbury House).

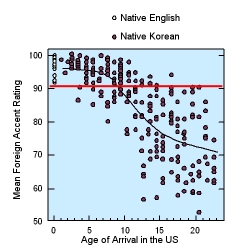

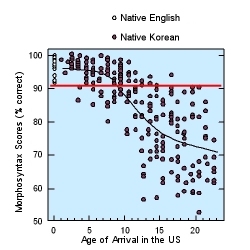

Basically, what happens in the first stage of adult vs child language learning (if both are faced with a new language) is that adults initially outperform children on almost all accounts, including pronunciation, comprehension, and production. But, just after the first stage, children and adolescents suddenly make the jump to lightspeed and literally leave their adult counterparts lightyears behind. Here are two graphs that show this quite clearly (re-created after Flege & Yeni-Komshian & Liu (1999) Age Constraints on Second Language Acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language 41):

The white dots in the top left corner are the native speakers. The fact that they are all clustered up there tells us that all the native speakers score between ~90-100% in tests on pronunciation and grammaticality. The spread of the brown dots shows that depending on when you get immersed in a language, you have a good chance of scoring as highly as a native speaker - or not. The red line represents the lowest score achieved by native speakers, the cut-off line if you will. Anyone below that line makes more ungrammatical sentences or has a recognisably foreign accent. This means ...

... that the first thing to go is correct acquisition of the sound system. If you expose young children under the age of 5 to a non-native language, almost all of them will not have much of a foreign accent. But this percentage drops rapidly and children exposed at the age of ten will not acquire the sound system as perfectly as native children. Once you hit 12-15, you basically end up with a mild foreign accent, start after 20 and you definitely will.

"Grammar" has a bit more of a window. Here essentially any child exposed to a new language before the age of 12 will acquire native like skills. However, if you wait until you're 15, you lose.

And strangely enough (or maybe not) for most adults the length of their exposure does little to affect their perceived foreign accent which seems to stick. So, train your tongue. And don't believe anyone who tells you that as an adult you can pick up a language "naturally" like a child does. It just doesn't work that way, not if you want to be good at it.

| Beagan gràmair | ||||||||||||

| ᚛ Pronunciation - Phonetics - Phonology - Morphology - Tense - Syntax - Corpus - Registers - Dialects - History - Terms and abbreviations ᚜ | ||||||||||||