An diofar eadar na mùthaidhean a rinneadh air "The Breaking of Long /e:/ or Feuchainn vs Fiachainn"

| (10 mùthaidhean eadar-mheadhanach le 2 chleachdaiche eile nach eil 10 'gan sealltainn) | |||

| Loidhne 1: | Loidhne 1: | ||

<span style="color: #008000;">''bial, sgial, ian, diag, ciad, sia, fiar, fiach, sgriach, briag, iadail, leum, beum, Seumas, ceum, leugh''</span> | <span style="color: #008000;">''bial, sgial, ian, diag, ciad, sia, fiar, fiach, sgriach, briag, iadail, leum, beum, Seumas, ceum, leugh''</span> | ||

| − | If some of you feel like scrambling for their dictionaries now, hang on | + | If some of you feel like scrambling for their dictionaries now, hang on. And those of you who are looking for a baseball bat to beat someone up - calm down. |

| − | + | Some or all of the above might not look familiar to you, but if you read the list aloud you'll suddenly realise what this is about. This is a peculiar business that <span style="color: #008000;">eu</span> is sometimes pronounced [ia] ... and sometimes not. | |

| − | So what is it all about and is there a rule? Well, sort of, but first | + | ==A bit of background== |

| + | So, what is it all about and is there a rule? Well, sort of, but first, let's depart into the foggy drizzle of Celtic historical linguistics and look at Common Gaelic, the ancestor of both modern Irish and Gaelic. Common Gaelic had words which contained a long [eː] sound: <span style="color: #6600CC;">béal, scéal, éan, déag, céad, sé, féar, féach, sgréach, bréag, éadail, léim, béim, Séamas, céim and léigh</span>. Most of these are still pronounced with a long [eː] in Irish dialects, except Munster Irish which has things like <span style="color: #6600CC;">céad</span> [kʲiad]). But, Scottish Gaelic, obviously thinking life was much too boring, did something more entertaining. It "broke" the long vowel. | ||

| − | This isn't quite as weird as it may sound | + | This isn't quite as weird as it may sound and it's very common in the world's languages. Think of English words like ''time'' and ''wine''. Great English Vowel Shift? Never heard of it? Well, those two words used to have a long [iː] sound - <span style="color: #6600CC;">tīma</span> and <span style="color: #6600CC;">wīn</span>. In English, when the vowels shifted around these became [ai], but in Gaelic [eː] became [ia]. And, having a Gaelic sense of humour, some rogue [eː] sounds decided to stay that way. |

| − | + | ==Never mind the background, how does it work?== | |

| + | Actually, there is sense behind it. We'll spare you the full story and just tell you how to know when to say [ia], and when not. Remember, in some ways this is a rule of thumb because it can depend to some degree on the dialect and even on the individual speaker who may choose to break their [eː] sounds, or not. So if you DO have a friend who says *Siamas instead of Seumas ... put aside thoughts of sending us a virus and simply accept it as "one of those things". | ||

Here's the rule: | Here's the rule: | ||

:(C')___(C') > [eː] and (C')___(C) > [ia] | :(C')___(C') > [eː] and (C')___(C) > [ia] | ||

| − | Stop sighing - all this means is that if the <eu> is followed by a broad consonant (C), chances are that the [eː] has turned into /ia/ and if the following | + | Stop sighing - all this means is that if the <eu> is followed by a broad consonant (C), chances are that the [eː] has turned into /ia/ and if the following consonant is slender (C') it is still [eː]. This accounts for beul, sgeul, eun, deug, ceud, feur, feuch, sgreuch, breug and eudail out of the above list - but what about the rest? |

| − | Well, if the /eː/ happens to be word final, it generally stays [eː] | + | Well, if the /eː/ happens to be word final, it generally stays [eː], for example, <span style="color: #008000;">gné, té, dé</span>. However, there are a few cases which must simply be learnt as exceptions, for example, <span style="color: #008000;">sia</span>. |

| − | + | ==Let me guess, there are exceptions?== | |

| + | Yaaas - this leaves a few oddballs like <span style="color: #008000;">ceum</span> and <span style="color: #008000;">leum</span> to be accounted for, which is easily done. Remember that Gaelic does not have a distinction anymore between broad and slender labials - b, p, f, m. So, what used to be <span style="color: #6600CC;">léim</span> became <span style="color: #008000;">leum</span> with a broad <span style="color: #008000;">m</span>, similarly <span style="color: #6600CC;">béim</span> » <span style="color: #008000;">beum</span>, <span style="color: #6600CC80;">céim</span> » <span style="color: #008000;">ceum</span> and <span style="color: #6600CC;">léigh</span> » <span style="color: #008000;">leugh</span>. | ||

| − | And then there | + | And then there's the tentative "rule" that if a word is high register, meaning that it's generally not used in everyday conversation but is restricted to "high functions" such as church or poetry, the pronunciation tends to be [eː]. Words like <span style="color: #008000;">beus</span> [beːs] or <span style="color: #008000;">ceusadh</span> [kʲeːsəɣ], which are quite restricted in their use, tend to have [eː]. |

| − | So why do we spell it <eu> and not <èa> or even <ia>? | + | ==That's a confusing way of spelling it, still...== |

| + | So why do we spell it <eu> and not <èa> or even <ia>? Because (on this occasion) being as efficient as the GOC board, the users of Common Gaelic hadn't quite worked out a standard spelling and so the Irish ended up with the <éa> variant and the Scots with the <eu>. | ||

| − | And why not <ia>? Well, because the GOC board of 1567 when the bible was translated into Gaelic was located in the Central Belt | + | And why not <ia>? Well, because the GOC board of 1567, when the bible was translated into Gaelic, was located in the Central Belt. That part of Scotland spoke dialects much closer to Irish and had retained the long [eː] ... so obviously they used <eu>. Only today, with the southern dialects being moribund or dead, and the majority of Gaels speaking Hebridean and Highland dialects, the spelling is slowly changing to reflect that. For example, sé for 'six' used be be quite commonly heard in Scotland, but now it's been completely replaced with sia, and everyone writes sgian not *sgéan. But some haven't quite made the switch and you'll see both feuchainn and fiachainn, yet few people would write *bial and *sgial. |

Should we? Well ... maybe, today it would certainly make sense. | Should we? Well ... maybe, today it would certainly make sense. | ||

| − | On the other hand, if we switched to writing <ia> instead of <eu> in all cases, we'd have | + | On the other hand, if we switched to writing <ia> instead of <eu>, in all cases, we'd have two small, but new, problems to contend with, both related to historic issues. Anyone guess what? The first problem regards words which have historically had <ia>, from well before <eu> broke into <ia>. They've always been <ia>, they're not derived from <eu>, and their second vowel has retained a schwa, [iə], as in iarr, siar etc. The second problem is that words with <ia> that derive from é/eu have a clear [a] vowel: [ia]. Point being? Well, if you write both <eu> and <ia> as <ia>, there is no way to tell from the spelling whether the correct pronunciation is [iə] or [ia]. |

| − | Now, for a native speaker that | + | Now, for a native speaker that's obviously no problem as he or she has fixed the correct sounds in their memory, rather than in the spelling. But it makes it tricky for learners. Also, even though some <eu> sounds have shifted in spelling to <ia>, they still form their genitives as if they were <eu> words: sgian > sgéin, fiadh > féidh etc. Incidentally, knowing this can help you pronounce words properly, so that if a word has <ia> in the nominative, and <éi> in the genitive, it will be pronounced [ia]. |

| − | Once again, there | + | Once again, there's no perfect answer ... |

| − | + | ==So where on earth?== | |

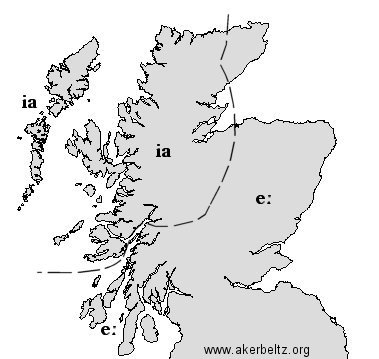

| − | This is merely an indication of where the majority of speakers break or don't break, a more detailed map shows that speakers break their long /eː/ | + | Here's a rough map of Scotland showing you where the boundary lies between these two areas: |

| + | |||

| + | [[Faidhle:ia.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

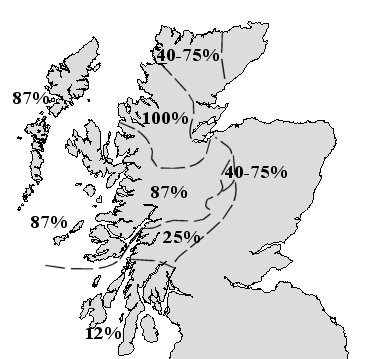

| + | This is merely an indication of where the majority of speakers break or don't break, a more detailed map shows that speakers break their long /eː/s to varying degrees: | ||

| + | [[Faidhle:ia2.jpg]] | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

{{BeaganGramair}} | {{BeaganGramair}} | ||

Am mùthadh mu dheireadh on 08:48, 15 dhen Dàmhair 2013

bial, sgial, ian, diag, ciad, sia, fiar, fiach, sgriach, briag, iadail, leum, beum, Seumas, ceum, leugh

If some of you feel like scrambling for their dictionaries now, hang on. And those of you who are looking for a baseball bat to beat someone up - calm down.

Some or all of the above might not look familiar to you, but if you read the list aloud you'll suddenly realise what this is about. This is a peculiar business that eu is sometimes pronounced [ia] ... and sometimes not.

A bit of background

So, what is it all about and is there a rule? Well, sort of, but first, let's depart into the foggy drizzle of Celtic historical linguistics and look at Common Gaelic, the ancestor of both modern Irish and Gaelic. Common Gaelic had words which contained a long [eː] sound: béal, scéal, éan, déag, céad, sé, féar, féach, sgréach, bréag, éadail, léim, béim, Séamas, céim and léigh. Most of these are still pronounced with a long [eː] in Irish dialects, except Munster Irish which has things like céad [kʲiad]). But, Scottish Gaelic, obviously thinking life was much too boring, did something more entertaining. It "broke" the long vowel.

This isn't quite as weird as it may sound and it's very common in the world's languages. Think of English words like time and wine. Great English Vowel Shift? Never heard of it? Well, those two words used to have a long [iː] sound - tīma and wīn. In English, when the vowels shifted around these became [ai], but in Gaelic [eː] became [ia]. And, having a Gaelic sense of humour, some rogue [eː] sounds decided to stay that way.

Never mind the background, how does it work?

Actually, there is sense behind it. We'll spare you the full story and just tell you how to know when to say [ia], and when not. Remember, in some ways this is a rule of thumb because it can depend to some degree on the dialect and even on the individual speaker who may choose to break their [eː] sounds, or not. So if you DO have a friend who says *Siamas instead of Seumas ... put aside thoughts of sending us a virus and simply accept it as "one of those things".

Here's the rule:

- (C')___(C') > [eː] and (C')___(C) > [ia]

Stop sighing - all this means is that if the <eu> is followed by a broad consonant (C), chances are that the [eː] has turned into /ia/ and if the following consonant is slender (C') it is still [eː]. This accounts for beul, sgeul, eun, deug, ceud, feur, feuch, sgreuch, breug and eudail out of the above list - but what about the rest?

Well, if the /eː/ happens to be word final, it generally stays [eː], for example, gné, té, dé. However, there are a few cases which must simply be learnt as exceptions, for example, sia.

Let me guess, there are exceptions?

Yaaas - this leaves a few oddballs like ceum and leum to be accounted for, which is easily done. Remember that Gaelic does not have a distinction anymore between broad and slender labials - b, p, f, m. So, what used to be léim became leum with a broad m, similarly béim » beum, céim » ceum and léigh » leugh.

And then there's the tentative "rule" that if a word is high register, meaning that it's generally not used in everyday conversation but is restricted to "high functions" such as church or poetry, the pronunciation tends to be [eː]. Words like beus [beːs] or ceusadh [kʲeːsəɣ], which are quite restricted in their use, tend to have [eː].

That's a confusing way of spelling it, still...

So why do we spell it <eu> and not <èa> or even <ia>? Because (on this occasion) being as efficient as the GOC board, the users of Common Gaelic hadn't quite worked out a standard spelling and so the Irish ended up with the <éa> variant and the Scots with the <eu>.

And why not <ia>? Well, because the GOC board of 1567, when the bible was translated into Gaelic, was located in the Central Belt. That part of Scotland spoke dialects much closer to Irish and had retained the long [eː] ... so obviously they used <eu>. Only today, with the southern dialects being moribund or dead, and the majority of Gaels speaking Hebridean and Highland dialects, the spelling is slowly changing to reflect that. For example, sé for 'six' used be be quite commonly heard in Scotland, but now it's been completely replaced with sia, and everyone writes sgian not *sgéan. But some haven't quite made the switch and you'll see both feuchainn and fiachainn, yet few people would write *bial and *sgial. Should we? Well ... maybe, today it would certainly make sense.

On the other hand, if we switched to writing <ia> instead of <eu>, in all cases, we'd have two small, but new, problems to contend with, both related to historic issues. Anyone guess what? The first problem regards words which have historically had <ia>, from well before <eu> broke into <ia>. They've always been <ia>, they're not derived from <eu>, and their second vowel has retained a schwa, [iə], as in iarr, siar etc. The second problem is that words with <ia> that derive from é/eu have a clear [a] vowel: [ia]. Point being? Well, if you write both <eu> and <ia> as <ia>, there is no way to tell from the spelling whether the correct pronunciation is [iə] or [ia].

Now, for a native speaker that's obviously no problem as he or she has fixed the correct sounds in their memory, rather than in the spelling. But it makes it tricky for learners. Also, even though some <eu> sounds have shifted in spelling to <ia>, they still form their genitives as if they were <eu> words: sgian > sgéin, fiadh > féidh etc. Incidentally, knowing this can help you pronounce words properly, so that if a word has <ia> in the nominative, and <éi> in the genitive, it will be pronounced [ia].

Once again, there's no perfect answer ...

So where on earth?

Here's a rough map of Scotland showing you where the boundary lies between these two areas:

This is merely an indication of where the majority of speakers break or don't break, a more detailed map shows that speakers break their long /eː/s to varying degrees:

| Beagan gràmair | ||||||||||||

| ᚛ Pronunciation - Phonetics - Phonology - Morphology - Tense - Syntax - Corpus - Registers - Dialects - History - Terms and abbreviations ᚜ | ||||||||||||