Labials or Sounds made at your Lips

This is isn't half as bad as what you have to learn about liquids. Trust me.

The word labial ultimately comes from the Latin word labium meaning lip and surprise, surprise, describes sounds which involve the lips. Gaelic just has four of these ... well, kind of because there's broad and slender, and lenition. OK, OK, maybe it's a bit more complicated than I made it sound at first, so one thing at a time.

Common Gaelic had 8 labials, plus their lenited fricatives: [b] [bʲ] [p] [pʲ] [f] [fʲ] [m] [mʲ] [v] [vʲ]. In modern Scottish Gaelic this has changed to [b] [bʲ] [p] [pj] [f] [fj] [m] [mj] [v] [vj].

B & P

The main difference between the old [b] (in pure IPA [b]) and the new [b] (in pure IPA [p]) is one of voice which we explained here earlier and the difference between modern Gaelic [b] (in pure IPA [p]) and [p] (in pure IPA [pʰ]) is one of aspiration which is explained on the same page. But to sum it up again:

| [b] - Devoiced unaspirated b | [p] - Voiceless aspirated p |

|---|---|

| English does not have this sound, it has the voiced [b] sound, meaning that your vocal chords vibrate. This English voiced b does not normally occur in Gaelic. The devoiced b you need for Gaelic does occur in English but only in clusters of <sp> such as in the word speech [sbiːʧ]. To make this sound, start with speech and leave out sounds until you are left just with the [b]. You can listen to this sound here. |

This is just like [p] in English so we won't say anything else about it. You can listen to some Gaelic examples here. |

[bʲ] ~ [bj]

So what's the [bʲ] ~ [bj] thing about?

Well, in Common Gaelic, [bʲ] was a voiced palatalised labial which was kind of a b with pursed lips, as it still is in Irish. However, in Gaelic, this slender [bʲ] has been lost except in certain circumstances where the [bj] sound is followed by a [j] glide. This happens when you get a formerly slender [bʲ] followed by a back vowel. Back vowel?

Back vowels

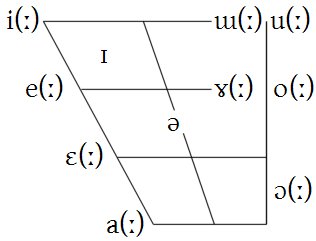

The vowels we make can be categorised according to where they are made in the mouth. Let's look at the following diagram:

If you start with [i] and then go down to [e] [ɛ] [a] and then over to [ɔ] [o] and [u] in one smooth transition, you will notice how the place of articulation moves way back in your mouth. That is why [ɔ] [o] and [u] are called back vowels. In Gaelic, the [aː] vowel also groups with the back vowels. Don't ask why. Well, OK, it's because as you move downwards in the diagram, your tongue not only moves back but it's also lowered. Because the distance between the two low vowels [a] and [ɑ] is so relatively small, languages which have only one a sound often group [a] with either front or back vowels.

To recapitulate, the back vowels in Gaelic are: [a] [ɔ] [o] [ɤ] [u] [ɯ]. This also includes diphthongs like [au] [ɔu] etc.

Examples

Sooo ... let's make this clearer with some examples:

| Slender b + back vowel | Slender b + front vowel | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| beàrn | [bjaːRN] | beinn | [beiNʲ] |

| beò | [bjɔː] | beum | [beːm] |

| biùro | [bjuːrɔ] | bidh | [biː] |

| Bealltainn | [bjauLdɪNʲ] | bean | [bɛn] |

There's one tricky issue: with vowels spelt ea, you only get the glide if the following consonant is 'strong' (for the want of a better term): [L] [N] [R] [Rʃd]

| ea + strong | ea + other | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| bealach | [bjaLəx] | beach | [bɛx] |

| beannachd | [bjaNəxɡ] | beanas | [bɛnəs] |

| beann | [bjauN] | bean | [bɛn] |

| beannag | [bjaNag] | beagan | [began] |

| bearradair | [bjaRədɛrʲ] | beachdachadh | [bɛxgəxəɣ] |

| beartach | [bjaRʃdəx] | bearach | [bɛrəx] |

Eu [eː] incidentally doesn't count - because it's not so much the spelling that governs this phenomenon but the pronunciation and eu is simply a long vowel. When broken into [ia] you do get a diphthong, but short [a] is not considered a back vowel so there's no glide in words like beul [biaL].

The same rules apply to the p's so we won't give them extra coverage here.

F & M

There's not much to say about these sounds as they are pronounced exactly as they are in English. Again, the rules stated for the glides, above, apply here too:

| Slender f/m + back vowel | Slender f/m + front vowel | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| feòil | [fjɔːl] | feusag | [fiasag] |

| meall | [mjauL] | féill | [feːLʲ] |

| feannag | [fjaNag] | mearachd | [mɛrəxg] |

As do the exceptions mentioned above, so all in all quite a regular bunch.

Leniting B P F M

Not too thorny an issue. This is the basic pattern:

| [b] ⇨ [v] | [bj] ⇨ [vj] |

| [p] ⇨ [f] | [pj] ⇨ [fj] |

| [f] ⇨ [ ] | [fj] ⇨ [j] |

| [m] ⇨ [v] | [mj] ⇨ [vj] |

If you had a glide in the unlenited word, you get a glide in the lenited word. Not too tricky. The only difficult bit to watch out for is f as it lenites to zero i.e. no sound at all. This is tricky for two reasons. First, because you have to get used to a sound which leaves no trace at all when lenited and that's unlike all other sounds which leave some sound behind when they lenite. And second, because there are two different outcomes depending on whether the lenition is caused by the definite article or something else in f clusters.

Normal F Lenition

With "normal" lenition, f just disappears:

| feòil | [fjɔːl] | m' fheòil | [mjɔːl] |

| fliuch | [flux] | ro fhliuch | [rɔ lux] |

| frasach | [frasəx] | glé fhrasach | [gleː rasəx] |

| fois | [fɔʃ] | m' fhois | [mɔʃ] |

Definite article lenition

But with the definite article, strange things happen. No surprises there. Well, not so strange but it's a pain having to watch out for something else. An [fl] or [fr] after the definite article, when the definite article causes lenition, strengthens to [Lʲ] and [R] respectively. Oh, and the [n] of the article strengthens to [Nʲ] and [N] respectively:

| fliuiche | [fluçə] | san fhliuiche | [səNʲ Lʲuçə] |

| fras | [fras] | san fhras | [səN Ras] |

This strengthening is something that happens quite regularly to the definite article. The other sound [fL] isn't affected because [fɫ] doesn't exist any more, unless you're from Harris, in which case you have [fɫ] which can strengthen to [fL]. If you speak a dialect which happens to allow slender [rʲ] in an initial cluster i.e. [frʲ], then you strengthen that to [R] too because initial slender and broad r are exactly the same. Quite logical all that really!!

| Beagan gràmair | ||||||||||||

| ᚛ Pronunciation - Phonetics - Phonology - Morphology - Tense - Syntax - Corpus - Registers - Dialects - History - Terms and abbreviations ᚜ | ||||||||||||