An diofar eadar na mùthaidhean a rinneadh air "Feasgar math or how to start an argument"

(Created page with "No, I'm only on a small sugar rush from the Christmas baking I've been eating. But there was a question on Facebook by someone and it triggered such a familiar debate, I figur...") |

|||

| (38 mùthadh eadar-mheadhanach le 2 chleachdaiche eile nach eil 38 'gan sealltainn) | |||

| Loidhne 1: | Loidhne 1: | ||

| − | No, I'm only on a small sugar rush from the Christmas baking I've been eating. But there was a question on Facebook | + | No, I'm only on a small sugar rush from the Christmas baking I've been eating. But there was a question on Facebook and it triggered such a familiar debate that I figured it's time for a write-up. |

| − | The question was about greetings and sure enough, someone mentioned feasgar math and a bit further on | + | The question was about greetings and sure enough, someone mentioned <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span> and a bit further on it got slated for non-Gaelic idiom. Emotions aside, it's an interesting question, so let's see if we can shed any light on the headache. |

| − | Virtually all textbooks and | + | Virtually all textbooks and phrase books from the turn of the century will give you <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> and <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span> for ''good morning'' and ''good afternoon''. There's also <span style="color: #008000;">oidhche mhath</span> but, curiously, that one does not seem to get the blood boiling. |

| − | To begin with, both madainn and feasgar are loanwords | + | To begin with, both <span style="color: #008000;">madainn</span> and <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar</span> are loanwords; very old loanwords, but still. They hail from the ecclesiastical sphere, where in the early days of the Celtic church, monks were presumably the first ever in the Gaelic world to chop up the day into defined time units beyond morning/midday/afternoon/night, all of which are relatively vague. These divisions are called the ''canonical hours'' and, while known across various confessions and flavours of church, there's the usual fight in a teacup over what the units are and when they are. Broadly, they are: |

| − | * Office of Readings ( | + | * Office of Readings ('''Matin'''s) |

* Morning prayer (Lauds) | * Morning prayer (Lauds) | ||

* Midmorning prayer (Terce) | * Midmorning prayer (Terce) | ||

* Midday prayer (Sext) | * Midday prayer (Sext) | ||

| − | * Midafternoon prayer (None) | + | * Midafternoon prayer ('''None''') |

| − | * Evening prayer ( | + | * Evening prayer ('''Vesper'''s) |

* Night Prayer (Compline) | * Night Prayer (Compline) | ||

| − | I'll sidestep the question about whether there's any point to that much praying but anyway, the Latin names of some of these time units were borrowed into Irish and Gaelic. Matins became madainn or maidinn, the None became nòin or tràth-nòin and Vespers became feasgar ( | + | I'll sidestep the question about whether there's any point to that much praying but, anyway, the Latin names of some of these time units were borrowed into Irish and Gaelic. Matins became <span style="color: #008000;">madainn</span> or <span style="color: #008000;">maidinn</span> (<span style="color: #6600CC;">maidin</span>, in Irish), the None became <span style="color: #008000;">nòin</span> or <span style="color: #008000;">tràth-nòin</span> (<span style="color: #6600CC;">iarnóin</span> for afternoon and <span style="color: #6600CC;">tráthnóna</span> for evening, in Irish), and Vespers became <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar</span> (though rare, in Irish, <span style="color: #6600CC;">feascar</span> in the common sense of the word and <span style="color: #6600CC;">easparta</span> in the religious sense). These were borrowed '''so''' long ago that the <span style="color: #008000;">p</span> became a <span style="color: #008000;">c/g</span>. |

| − | Now this is where it gets tricky | + | Now, this is where it gets tricky because we don't really have much evidence of these being used in greetings. Partly due to a lack of colloquial texts in the older material. However, in texts from the 1800s, we do have instances of the still ubiquitous Irish greeting, <span style="color: #6600CC;">Dia dhuit</span>, ''God be with you''. |

| − | It is | + | It is certainly conceivable that in pre-Reformation Gaelic speaking Scotland this phrase was also in common use but that's just an educated guess. Either way, it has not been heard much in Gaelic Scotland for at least a century, otherwise it would have found its way into some of the older phrase books and dictionaries. |

| − | So what | + | So, what filled its place? Excellent question. Nobody seems to be quite sure. When you ask native speakers who dislike <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> or <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span>, they're usually stuck for an alternative. They would have no hesitation about greeting someone they know by name - variations of <span style="color: #008000;">A Dhòmhnaill, fada on uairsin</span> or <span style="color: #008000;">A Mhàiri, dè do chor an-diugh?</span>. But ask them how to address someone they don't know by name and silence is usually what you get. ''Hi'' and ''hello'' (however you re-spell them) are used, but they're clearly English in origin. Some suggest <span style="color: #008000;">latha math dhuibh</span> but others reject it. Some suggest a reference to the weather, such as <span style="color: #008000;">latha math a th' ann</span>, yet others claim they'd never use that. Though at least for this last one we have some evidence of usage. Nan MacKinnon, whom no one can accuse of having poor Gaelic, tells a story (<span style="color: #008000;">Gibht na mnà-glùine</span>) where a woman meets a stranger on her way late at night to Eoligarry: |

| + | :<span style="color: #008000;">... shaoil i gur e duine nàdarra a bh' ann agus thuirt i "Tha oidhche mhath ann".</span> | ||

| + | :<span style="color: #008000;">"Tha," os e fhèin, ...</span> | ||

| + | Also, slightly more recent and much more explicity as a means of addressing a '''stranger''', this anecdote from the Cape Breton magazine ''Am Bràighe'': | ||

| + | [[Faidhle:latha math.png|center]] | ||

| − | + | This bring us to the other part of the problem - the historic decline in speaker numbers through genocide (you know, dispossession, forced emigration, economic deprivation and forced anglicisation via the education system). These circumstances resulted in a society where you could no longer assume that a stranger you met was Gaelic speaking and consequently you would not commonly address them in Gaelic, but in English. | |

| − | + | As it stands, the oldest incident of <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span> I could find in a hurry was in MacDougall's ''Folk Tales and Fairy Lore'' from 1910: | |

| + | [[Faidhle:feasgar math.png|center]] | ||

| − | In this spirit, I bid you all oidhche mhath. | + | and <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> in an 1892 edition of the Canadian Gaelic newspaper Mac-Talla: |

| + | [[Faidhle:maduinn mhath.png|center]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first appearance in textbooks seems to date to that period too, for example this in the 1892 <span style="color: #008000;">Còmhraidhean ann an Gàidhlig 's am Beurla</span>: | ||

| + | [[Faidhle:feasgar math2.png|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Relatively old but given that Gaels have written things down since the 6th century, it's so novel the paint is hardly dry. Like calling a word that was first used in Windows 3.1 "ancient". | ||

| + | |||

| + | We will probably never know exactly who came up with <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> and <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span> but they're certainly here to stay. They just jar a bit with some older native speakers. With a native speaker, my personal solution to the headache is to move off <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> and <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span> as soon as I know their name. Using their name in the vocative, followed by a variety of introductory questions such as <span style="color: #008000;">dè do chor/ur cor, ciamar a tha thu/sibh</span>, and so on, seems to go down relatively well. <span style="color: #008000;">Sin thu/sibh</span> or the more colloquial <span style="color: #008000;">shin thu</span> also works. That way, personally, I haven't had the <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> debate in years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Alternatively, you can take the standpoint that there are enough people, including native speakers, for whom <span style="color: #008000;">madainn mhath</span> and <span style="color: #008000;">feasgar math</span> are perfectly natural Gaelic today and that whatever may have been the case once no longer applies today. Which is also a perfectly permissible approach - just be prepared for an argument from some quarters! | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this spirit, I bid you all <span style="color: #008000;">oidhche mhath</span>. | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | {{BeaganGramair}} | ||

Am mùthadh mu dheireadh on 14:57, 9 dhen Mhàrt 2020

No, I'm only on a small sugar rush from the Christmas baking I've been eating. But there was a question on Facebook and it triggered such a familiar debate that I figured it's time for a write-up.

The question was about greetings and sure enough, someone mentioned feasgar math and a bit further on it got slated for non-Gaelic idiom. Emotions aside, it's an interesting question, so let's see if we can shed any light on the headache.

Virtually all textbooks and phrase books from the turn of the century will give you madainn mhath and feasgar math for good morning and good afternoon. There's also oidhche mhath but, curiously, that one does not seem to get the blood boiling.

To begin with, both madainn and feasgar are loanwords; very old loanwords, but still. They hail from the ecclesiastical sphere, where in the early days of the Celtic church, monks were presumably the first ever in the Gaelic world to chop up the day into defined time units beyond morning/midday/afternoon/night, all of which are relatively vague. These divisions are called the canonical hours and, while known across various confessions and flavours of church, there's the usual fight in a teacup over what the units are and when they are. Broadly, they are:

- Office of Readings (Matins)

- Morning prayer (Lauds)

- Midmorning prayer (Terce)

- Midday prayer (Sext)

- Midafternoon prayer (None)

- Evening prayer (Vespers)

- Night Prayer (Compline)

I'll sidestep the question about whether there's any point to that much praying but, anyway, the Latin names of some of these time units were borrowed into Irish and Gaelic. Matins became madainn or maidinn (maidin, in Irish), the None became nòin or tràth-nòin (iarnóin for afternoon and tráthnóna for evening, in Irish), and Vespers became feasgar (though rare, in Irish, feascar in the common sense of the word and easparta in the religious sense). These were borrowed so long ago that the p became a c/g.

Now, this is where it gets tricky because we don't really have much evidence of these being used in greetings. Partly due to a lack of colloquial texts in the older material. However, in texts from the 1800s, we do have instances of the still ubiquitous Irish greeting, Dia dhuit, God be with you.

It is certainly conceivable that in pre-Reformation Gaelic speaking Scotland this phrase was also in common use but that's just an educated guess. Either way, it has not been heard much in Gaelic Scotland for at least a century, otherwise it would have found its way into some of the older phrase books and dictionaries.

So, what filled its place? Excellent question. Nobody seems to be quite sure. When you ask native speakers who dislike madainn mhath or feasgar math, they're usually stuck for an alternative. They would have no hesitation about greeting someone they know by name - variations of A Dhòmhnaill, fada on uairsin or A Mhàiri, dè do chor an-diugh?. But ask them how to address someone they don't know by name and silence is usually what you get. Hi and hello (however you re-spell them) are used, but they're clearly English in origin. Some suggest latha math dhuibh but others reject it. Some suggest a reference to the weather, such as latha math a th' ann, yet others claim they'd never use that. Though at least for this last one we have some evidence of usage. Nan MacKinnon, whom no one can accuse of having poor Gaelic, tells a story (Gibht na mnà-glùine) where a woman meets a stranger on her way late at night to Eoligarry:

- ... shaoil i gur e duine nàdarra a bh' ann agus thuirt i "Tha oidhche mhath ann".

- "Tha," os e fhèin, ...

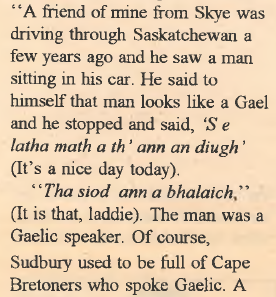

Also, slightly more recent and much more explicity as a means of addressing a stranger, this anecdote from the Cape Breton magazine Am Bràighe:

This bring us to the other part of the problem - the historic decline in speaker numbers through genocide (you know, dispossession, forced emigration, economic deprivation and forced anglicisation via the education system). These circumstances resulted in a society where you could no longer assume that a stranger you met was Gaelic speaking and consequently you would not commonly address them in Gaelic, but in English.

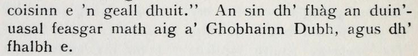

As it stands, the oldest incident of feasgar math I could find in a hurry was in MacDougall's Folk Tales and Fairy Lore from 1910:

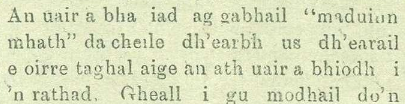

and madainn mhath in an 1892 edition of the Canadian Gaelic newspaper Mac-Talla:

.

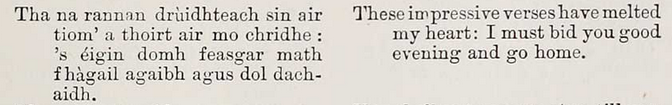

The first appearance in textbooks seems to date to that period too, for example this in the 1892 Còmhraidhean ann an Gàidhlig 's am Beurla:

Relatively old but given that Gaels have written things down since the 6th century, it's so novel the paint is hardly dry. Like calling a word that was first used in Windows 3.1 "ancient".

We will probably never know exactly who came up with madainn mhath and feasgar math but they're certainly here to stay. They just jar a bit with some older native speakers. With a native speaker, my personal solution to the headache is to move off madainn mhath and feasgar math as soon as I know their name. Using their name in the vocative, followed by a variety of introductory questions such as dè do chor/ur cor, ciamar a tha thu/sibh, and so on, seems to go down relatively well. Sin thu/sibh or the more colloquial shin thu also works. That way, personally, I haven't had the madainn mhath debate in years.

Alternatively, you can take the standpoint that there are enough people, including native speakers, for whom madainn mhath and feasgar math are perfectly natural Gaelic today and that whatever may have been the case once no longer applies today. Which is also a perfectly permissible approach - just be prepared for an argument from some quarters!

In this spirit, I bid you all oidhche mhath.

| Beagan gràmair | ||||||||||||

| ᚛ Pronunciation - Phonetics - Phonology - Morphology - Tense - Syntax - Corpus - Registers - Dialects - History - Terms and abbreviations ᚜ | ||||||||||||